In the 2010s, Britain was obsessed with benefits. The coalition government launched a crackdown on benefit fraud - which was costing over £1 billion a year. George Osbourne spoke out against those “sleeping off a life on benefits”. Channel 4 debuted Benefits Street, a negative documentary about those living on the dole.

The widespread public perception was that there was a subset of the population that were lazy scroungers, collecting a benefits payslip rather than working.

The often misunderstood fact about benefits, though, was that many claimants at that time were in work, and using benefits to supplement their low incomes. Between 2005 and 2015, the national living wage rose by about £1.50 an hour (in the same period since 2015, it’s risen by almost £6 an hour). Low-wage work was prevalent, and there was a surge in largely unregulated gig work and zero-hours contracts.

In other words, the state was supplementing private enterprise’s access to cheap labour (why do you think Ubers used to be so cheap!).

We were led to believe that people were shirkers: when many were actually badly-paid workers.

In fact the number of people claiming unemployment-related benefits was pretty consistently falling - that is, until COVID.

But COVID seemed to trigger something in the national psyche. Benefits Britain is back with a bang.

Sick

The 2025 benefits claimant is not searching for work, or even claiming to be. They’re not using benefits to top up a low income. They’re sick - likely with a mental illness - and signed off work in perpetuity.

In the past five years, the number of people out of work due to long-term sickness has increased by 714,000. Now, almost 3 million working-age Brits stay at home, unable to work due to poor health. 160,000 of those are under the age of 24. If the trend continues, by 2030 - we’ll pay more on their benefits than we paid on defence last year.

But this can’t be right, can it? In a time when most of the world has got healthier, and most work has become more flexible, more people than ever say they can’t work?

What is going on?

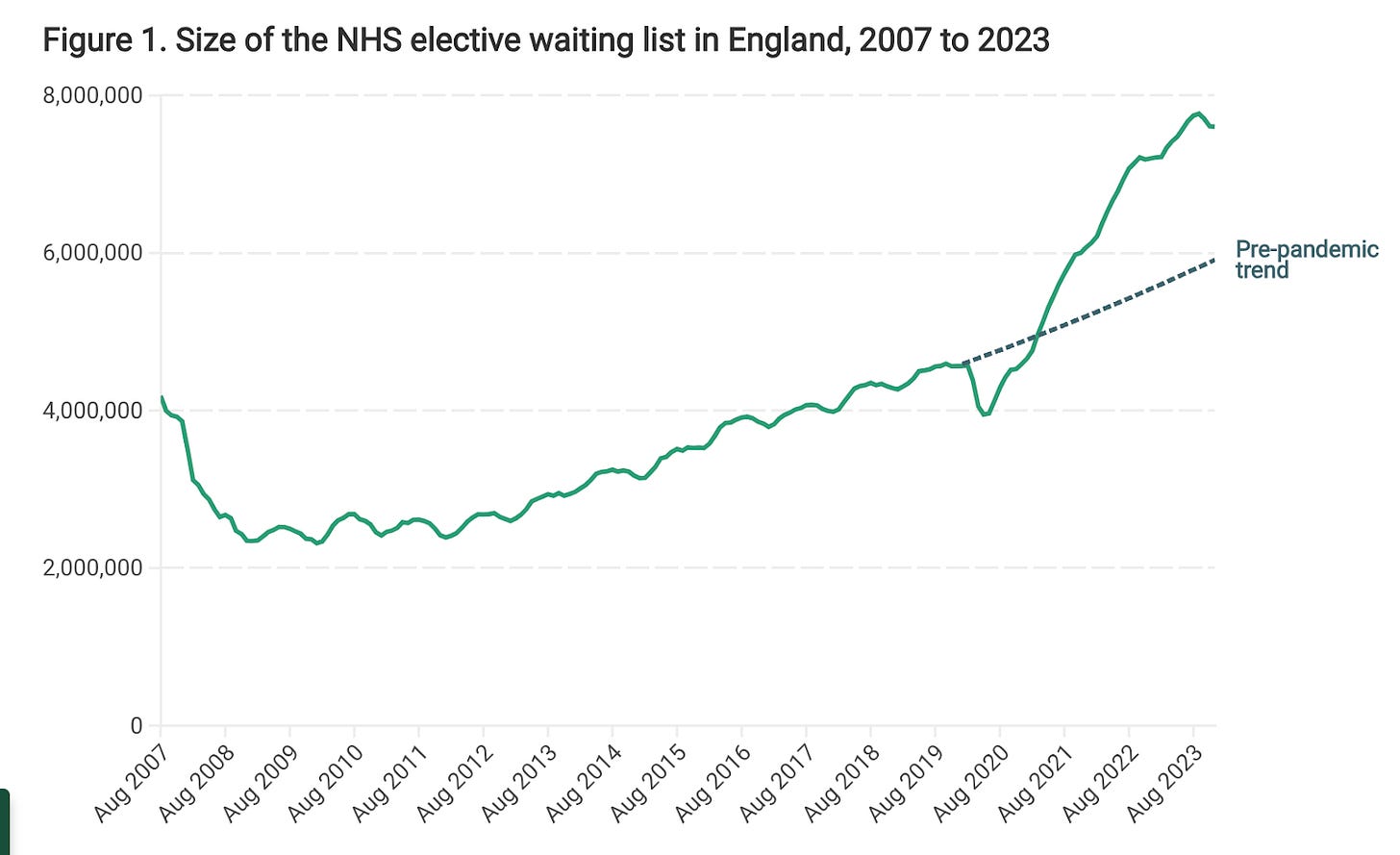

Maybe the NHS waiting list is to blame. More than 7 million people are waiting for treatment - a pretty astronomical spike since COVID.

Even when someone gets to the front of the queue, many people are finding the NHS is not well-suited to treating them. As I’ve written before, there is enormous growth in chronic conditions like diabetes, mental illness and chronic pain.

But bizarrely, over the last decade, most measures of our general national level of wellness haven’t really changed. We’re about as healthy as we were a decade ago. Indeed, the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee found “no convincing evidence that the main driver of the rise in these benefits is deteriorating health or high NHS waiting lists.”

Can’t work, won’t work

The government is clearly handing out these benefits too generously. Four out of five incapacity benefit claims are successful. It took me five minutes to find a website that would, for a fee, guide me through the entire process to ensure I got the maximum payout. If you play your cards right, you can claim £23,899 a year in health-related benefits with no expectation to work or even look for work. That’s higher than the minimum wage.

Now, of course some people really are too sick to work, or have a disability that prevents them from working. But, frankly, there is no evidence that 3 million people meet that criteria. It’s hard to believe that almost a million people were working this time 5 years ago, but have now developed an illness that completely shuts them out from the working world: there’s just no evidence that has happened.

The only conclusion you can draw, then, is that many of the people receiving health-related benefits could work.

It’s not just for the sake of the economy, or even the sake of fairness, that people who can work should work. Handing out sickness benefits to people who could work is bad for the individuals themselves. Work offers so many benefits - not least dignity, opportunity and development, while unemployment is proven to be bad for your mental and physical health.

For young people this is especially dangerous. If they miss out on that crucial first job, they are likely to never work in their lives. That’s at a huge cost to the taxpayer, and a detriment to their quality of life.

Part of this is caused by an explosion in diagnoses. From 2020 to 2023, there has been a 400% rise in adults seeking a diagnosis of ADHD: twenty years ago, ADHD was not even considered an illness that adults could be diagnosed with. The majority of these cases are not severe, they are moderate. What once sat in the normal spectrum of personality and behaviour, is now a diagnosis - which entitles

What nobody asks is whether these diagnoses, and the behaviours they unlock, are actually good for the sufferer. It’s deeply concerning that people who exhibit symptoms of a mental illness - like anxiety or ADHD - are building their identity around a diagnoses, developing norms that make their symptoms worse (like avoiding anxiety-inducing situations), and - more and more - signing off from work. For most people, the worst treatment for their illness is exclusion and isolation. Yet we have a benefits system that encourages exactly that.

What next?

This isn’t about taking benefits away, it’s about fixing the perverse incentive structure. People should be encouraged into work and opportunity rather than incentivised to stay out of work. We should support people who can only work a little bit, or need to work in particular patterns or with adjustments into jobs that are right for them.

How much better would it be, for example, if the government invested in work coaches that can support people with what they need to get into work, whether that’s treatment, training or adjustments, rather than paying millions to stay out of work. That’s why moves like the “Right to Try” - that lets people in receipt of disability benefit try getting back to work without a penalty - are a great idea.

The risk is that this will brew into a scandal that demonises people who really are in need of these benefits. That scandal is already fomenting. The Motability scheme gives people in receipt of disability benefits access to a taxpayer-funded car of their choice. It’s not immediately clear why many of these ‘new disabled’ claimants with anxiety and ADHD would need a taxpayer-funded BMW. One in five new cars sold last year were sold through the Motability scheme.

At the same time, the number of children getting SEND diagnoses is skyrocketing. Councils are paying for 31,000 children to take private taxis to and from school, who are diagnosed with conditions: the vast majority of councils are spending more on these taxis than they are on road repairs.

For a country that, by every metric, is just as healthy as it was a decade ago, the number of disability claimants is fairly shocking. No doubt some are exploiting the system, but I suspect the majority are being let down by it: receiving a diagnosis that does them more harm than good, or being incentivised to cut themselves off rather than integrate into mainstream society.

Labour are to-ing and fro-ing over changes to sickness and disability benefits but change is urgently needed and it’s needed fast: for the sake of fairness for everyone.

A really interesting and quite shocking read but not surprised.